Conducting Brahms: an approach to the opening of the first symphony

By Gianmaria Griglio

When young conductors approach a score for the first time the omnipresent question is: how do I begin?

In a case of a repertoire symphony such as Brahms's first, the self-comparison with historical recordings is bound to make your knees tremble and even inadequate to the task. A good starting point is the analysis of the piece, which will give you an overall view of the musical arch, help you spot the turning points of the score, and bring out the technical challenges.

One of them, for instance, is the choice of tempo; another one is balance. One resulting issue of this is which part to bring out (or not) when there is a potential balance problem strictly connected to the tempo choice. All of this hits you right in the stomach at the very beginning of Brahms' first symphony.

Let's start at the very top:

Tempo choice

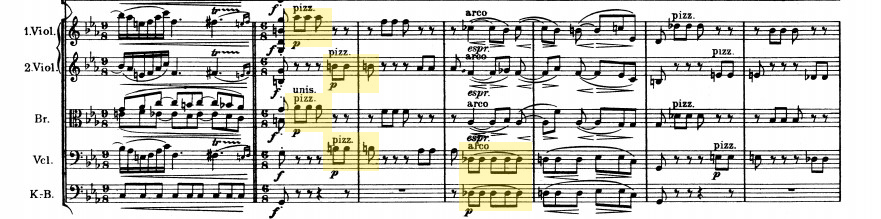

The marking is " Un poco sostenuto ", which, literally, translates to "slightly sustained ". Now, that's the first riddle that needs to be solved. Let's take a look at the score: everything in the score is marked as legato; even the double basses, doubling the timpani with those pulsing eight notes, are slurred by the bar; if you go too fast they will have no chance of separating the notes within the slur, thus missing also the pesante (heavy) indication, and everything will turn into muddy chaos.

On the other hand, too slow of a tempo will prevent the natural flowing of the melodic lines and the music will die before the end of the first phrase; look at bar 9 for a cue (highlighted in the picture below): the writing seems quite static but the syncopations in the woodwinds hold an implicit tension that too slow of a tempo will forfeit.

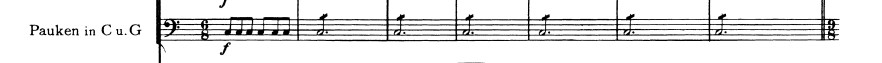

Another clue is to look for what gives continuity to the music during this introduction: for me, it's clearly the iconic pulsing of the timpani in the first 8 bars.

Those eight notes are transferred to the pizzicatos in the strings in bar 9 and then back to slurred notes to the double basses and cellos in bar 11, and the process repeats for almost the entire introduction. If you think of it this way, the color and the sound that you will expect for those notes will change, looking for something heavier and closer to the darkness of the timpani. Consequently, your gestures will be somewhat heavier too: after all, as a conductor, you're molding sound, right?

So...how do we establish the right tempo?

Having said that, I wouldn't dream of suggesting a metronomic playing of this introduction. Rather, think about how you would sing it, where you would take a breath. Sing the beginning, then move to bar 9 (the pizz), then to bars 19-20, then to bar 29: these are the key points that will give you the "correct tempos" in which you can move around.

Brahms was a great admirer of Beethoven: his musical forms are crystal clear and instruments always imitate the voice or, at least, strive to. Yet, Brahms is obviously not Beethoven, and his musical language and expressivity are fully immersed in the romantic era. As one of my teachers once told me, when you conduct Brahms you have to feel him as a romantic but play him as a classic.

Tough balance. But: if the aforementioned points work well together without disrupting the continuity of the music line then you're in a very good spot. Of course, after this, you will still have to manage the correlation between the introduction and the Allegro. Something else to think about.

Technically speaking, at the very beginning you need to focus on the pulsing: make a connection with the timpani player and clearly establish the tempo. Once that's done, which basically means a clear upbeat and a clear pulse for the first 2-3 eight notes, get out of the way and focus on the other two lines.

Balance

The balance of the introduction is another key factor in a successful reading of this symphony. Clearly there are three lines to take into consideration: the descending line in the woodwinds, the ascending line in the strings, the pulsing of the timpani.

Technical tip: make sure everyone is only playing forte and not fortissimo or you will have no place to go later on.

Is there a line that's more important than another? The answer is no. But why? Well, let's take a look at the orchestration:

The descending line

The descending line of the woodwinds is reinforced in by the violas and partially by the 3rd and 4th horn. The horns enhance the chromatic tension and then rest. Why adding the violas to the mix for the entire duration of the first phrase? First of all, violas mix very well with the clarinets: the two sections often complement each other in color and make for a very dark and warm tone; but giving the violas the line of the woodwinds also allows Brahms to introduce an element of automatic balance: the descending line "infiltrates" itself right into the ascending line part of the orchestra, like a spy behind enemy lines.

The ascending line

In full contrast, pulling away from the woodwinds and violas, the violins and cellos push towards their high registers, spanning 2 full octaves in doublings. Look at the cellos part: they are not playing in the lower register, the part is written in tenor clef and they go up in a register where the sound of the instrument is clearly audible, warm and full of tension at the same time, avoiding the "mud" of the lower overtones.

Technical tip: pulse on beat 5 in bar 2 and 3, it will help the strings get off the slurs all at the same time.

The pulsing line

The glue to the two previous lines is a C pedal of the first and second horn, which is pulsed through by the contrabassoon, the basses, and especially the timpani. Why especially? The other instruments offer a sort of magmatic base but due to their nature, they would never be able to come through as clearly as the timpani. Notice also the trumpets: they play two Cs in octaves in the first bar and then rest: this adds a certain " calling" weight to the sonority of the opening chord but then leaves the attention to the rest of the line.

All in all, this is one example of a piece in which a conductor could really get in the way: Brahms takes care of the balance for us. If everyone plays just forte the balance is already in the orchestration and all three lines will come through and be perfectly heard. Sometimes you just have to let the players play and enjoy the ride. 🙂

After you've figured out all of this, you've still only covered a few bars. And what about the tempo change between the introduction and the Allegro? What's the correlation between the two? Is there a mathematical proportion in the tempos?

I feel this is a subject for another post. But: giving that tempo changes are a huge part of conducting, I've dedicated an entire chapter of my "Pass the baton" video course, created exclusively for iClassical-Academy, to it.

You will learn, among other things :

- how to give a pulse to the orchestra (the single most important technical aspect of conducting)

- how to approach and solve tempo changes problems

- how to read a score in a visual way in order to "use" the orchestration to shape your gestures

Have fun!

Gianmaria Griglio

Winner of a fellowship at the Bayreuther Festspiele, Gianmaria Griglio’s conducting has been praised for his “energy” and “fine details”, quickly captivating his audiences time and again with his vibrant and dynamic interpretations. Long an advocate of contemporary music, Gianmaria Griglio took part in the first recording of music by American composer Irwin Bazelon, conducted the world premiere of Harold Farberman’s opera The Song of Eddie, a candidate for the Pulitzer Prize, and has served as Music Director of International Opera Theater Philadelphia for four years, in addition, to appear as guest conductor of many orchestras around the world. Gianmaria has been invited regularly as a guest teacher at the Conductors Institute, at Bard College, NY.

Winner of a fellowship at the Bayreuther Festspiele, Gianmaria Griglio’s conducting has been praised for his “energy” and “fine details”, quickly captivating his audiences time and again with his vibrant and dynamic interpretations. Long an advocate of contemporary music, Gianmaria Griglio took part in the first recording of music by American composer Irwin Bazelon, conducted the world premiere of Harold Farberman’s opera The Song of Eddie, a candidate for the Pulitzer Prize, and has served as Music Director of International Opera Theater Philadelphia for four years, in addition, to appear as guest conductor of many orchestras around the world. Gianmaria has been invited regularly as a guest teacher at the Conductors Institute, at Bard College, NY.

Gianmaria Griglio is presently Music Director of Opera Odyssey.

A new perspective on conducting technique - an online conducting course

GianMaria Griglio created the course "Pass the Baton" for iClassical Academy.

Take your conducting to the next level by learning how to break patterns in a logical and practical way: you will learn how to look at a score from a different point of view, building your technique from the music itself, and becoming much more effective in your conducting.