Piazzolla and Ginastera: two contrasting sides of Argentine Music

by Guillermo Scarabino

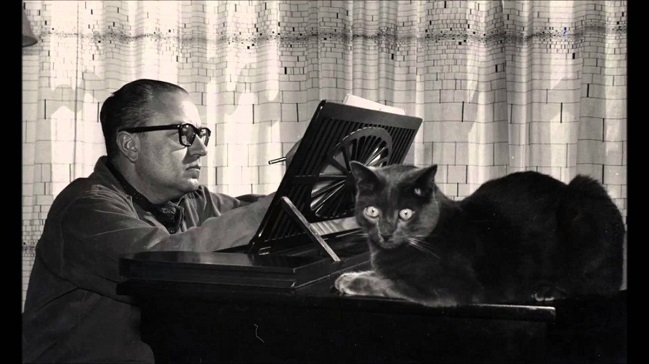

Maestro Guillermo Scarabino met Astor Piazzolla and Alberto Ginastera in person during his long-lasting conducting career.

He premiered in Argentina Ginastera’s “Popol Vuh: The Creation of the Mayan World, Op. 44”; a symphonic poem in seven movements in Argentina in 1995; a work originally commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra under the conductor Eugene Ormandy in 1975.

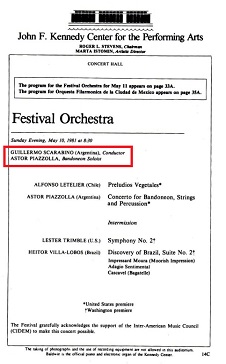

Also, he conducted the orchestra with Piazzolla as the soloist in the U.S. premiere of the latter’s Concerto for Bandoneon.

In this article, Maestro Sarabino takes you on a journey to discover more about these great artistic personages, remembers wonderful encounters with the composers, and how Arthur Rubinstein brought the two most widely known Argentine composers together.

Ginastera and Piazzolla; the most widely known Argentine composers in the world

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983) and Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) are the most widely known Argentine composers in the world. Both reflect the influence of the popular music of their country, although in different ways.

In his beginnings, Ginastera was a continuation of the so-called "nationalist" school, initiated at the end of the 19th century by Alberto Williams (1862-1962) and other composers of the time. In Ginastera's academic works prior to the 1960s, there is a great deal of music originating in rural popular music: malambo, triste, chacarera, gato, zamba, vidala, etc. Years later, he drifted towards a more universal language, using techniques such as atonalism, dodecaphonism, chance music, etc. But even in works such as the Piano Concerto No. 1 Op 28, dodecaphonic, it is easy to detect the rhythmic influence of, for example, the malambo species.

Alberto Ginastera ©Library of Congress Washington

Piazzolla, on the other hand, in his early days clearly separated the languages: his academic compositions tended towards a universal neoclassical language, while what constituted his livelihood as a composer, arranger, bandoneonist, and conductor were strongly rooted in tango, the archetypal species of Argentine urban popular music.

Different developments and background

Their respective formations followed very different paths: Ginastera was born and resided in Buenos Aires, studying music from childhood at a private Conservatory founded in 1893 by the aforementioned Alberto Williams. Before entering the National Conservatory in 1936, Alberto had already written several works that he later withdrew from the catalog. His "official" Op 1, the ballet Panambí, was premiered in July 1940 at the Teatro Colón, with musical direction by Juan José Castro and choreography by Margarita Wallman.

On the other hand, Piazzolla was born in Mar del Plata and lived with his parents for some years in the slums of New York: between 1925 and 1930 in Greenwich Village, and between 1932 and 1936 in Little Italy. He settled in Buenos Aires only in 1937, at the age of 16. His New York years took place during Prohibition, the Great Depression, and the heyday of the Cosa nostra.

While Ginastera grew up in the bosom of a bourgeois family, sheltered by Argentina's intelligentsia, Astor lived the experience of being part of street gangs of teenagers who often settled their differences with fist blows. From those years, he remembered that in the hairdresser's where his mother worked, women from rival mafia families were attended to on different days to avoid them meeting there, or that his father clandestinely transported alcoholic beverages in a camouflaged tank on the sidecar seat of a motorcycle, on which he sat to give a "family" touch to the trip and not arouse suspicions.

Piazzolla was quite self-taught for his initial musical training, despite the lessons he received from Bela Wilda (a Hungarian classical pianist). Jazz, a style completely foreign to Ginastera, also had a strong influence on his training.

Mediation of Arthur Rubinstein

Ginastera and Piazzolla came into contact thanks to Arthur Rubinstein's mediation, who, while in Buenos Aires in 1940, was kind enough to receive Piazzolla and read some of his "serious" youthful compositions. Rubinstein recognized that there was talent there and introduced him to Juan José Castro, who suggested that he study with his protégé Alberto Ginastera. Interestingly, Alberto was Astor's first formal teacher, and Astor, Alberto's first private student.

Piazzolla studied with Ginastera until 1946: with him, he learned the techniques of counterpoint, harmony, composition, and orchestration in the tradition of the Paris Conservatoire, which at that time influenced the National Conservatory of Argentina, from which Ginastera had graduated a couple of years earlier.

A faint Ginastera presence is recognizable in Piazzolla's pre-1954 compositions. For example, the "Danza" from Contemplación y Danza for clarinet and strings has in its harmonic and rhythmic DNA "genetic material" typical of Ginastera's rural style, just as in the "Contemplación" from the same work or in the "Pastoral" from the Suite for Oboe and Strings, a subtle aroma of jazz can be breathed. Of course, after his time in the mid-1950s at the boulangerie -as Nadia Boulanger's school was laughingly called- Piazzolla concentrated his greatest creative and interpretative efforts on tango.

It is known that it was the legendary French teacher who persuaded him that this was his most genuine language and that he should not abandon it. Piazzolla was fought by traditionalists when his so-called "tangos" ceased to be danceable. Still, the music of Buenos Aires was always his medium, in his tangatas, tangazos, tanguedias, ballads, and songs.

Piazzolla had no influence on Ginastera, whose relationship with tango was scarce, practically null. He approached it in a symphony called Porteña of 1942, later withdrawn from the catalog and in his catalog survived only a brief tango reminiscence in the eighth of the 12 Preludes for Piano Op 12 (1944).

I knew both composers, although I did not have the opportunity to meet them frequently. As a conductor, I performed many of their works, including some on memorable occasions. In the case of Ginastera, for example, in 1995, it was my turn to premiere in Argentina with the Orquesta Filarmónica de Buenos Aires his Popol Vuh Op 44, and in 2016 to conduct the performances of the opera Beatrix Cenci Op 38, staged at the Teatro Colón to celebrate the centenary of his birth, with the stage direction of Alejandro Tantanián. As for Piazzolla, I collaborated with him in the U.S. premiere of his Concerto for Bandoneón and Orchestra, which took place at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. in 1981 and, the following year, on a similar occasion at a Festival in Puerto Rico. Ginastera was a man whose very presence commanded solemn respect, to the point that, when he founded and was the first Dean of the Faculty of Music at the Catholic University of Argentina (1959), we, his students and other young musicians began to call him "El Obispo" (The Bishop).

The last time I saw him was in 1966, in one of the performances of his first opera Don Rodrigo Op 31, in the inaugural season of the New York City Opera in its new Lincoln Center venue (incidentally, that title meant Plácido Domingo's New York debut). I was to meet him in the lobby to receive an invitation from his hands. When I approached him, he was chatting amiably with George Balanchine, Director of the New York City Ballet. As soon as I entered the box, I discovered that my seat neighbor was Erich Leinsdorf, then Director of the Boston Symphony: that was Ginastera's socio-professional world.

In contrast, I met Piazzolla at Dulles Airport in Washington D.C. under almost comical circumstances. We had gone to meet him with an official of the Organization of American States in a car driven by him. We were surprised to see him arrive with a bandaged finger: he had slightly injured himself trying to squash what he thought was an insect on the wall, and it turned out to be a protruding nail. Loaded with luggage and in the car, there was no way to get it started, much to the despair of the OAS official. Piazzolla offered to push with me. We made several unsuccessful attempts while he, between pushes and pushes and without losing his good humor, uttered a string of expletives in the purest slang of the Porteño night. An absolutely unimaginable movie gag with Ginastera as the protagonist...

About the author

Guillermo Scarabino was the Director of Artistic Production of the Teatro Colon Buenos Aires for many years. He is a well-respected conductor and was a Juror member at several editions of the International Alberto Ginastera Composition Competitions.

Guillermo Scarabino was the Director of Artistic Production of the Teatro Colon Buenos Aires for many years. He is a well-respected conductor and was a Juror member at several editions of the International Alberto Ginastera Composition Competitions.

Furthermore, he taught at the Mendoza Summer Conducting Courses, at the International Summer Academy of Concepción (Chile), and at Venezuela’s Inter-American Conducting Courses. Maestro Scarabino is also a lecturer and author.

He graduated from the University of Rosario (Argentina), obtaining a Master of Arts Degree in Music Theory at the Eastman School of Music (Rochester, NY).

Violin for Tango Master Course - New Musical Jewel

Master Teachers

Rafaelo Gintoli

Javier Weintraub

Ensemble Estacion Buenos Aires

Language

Spanish with English & Spanish subtitles

Description Jewel

On the occasion of Astor PIAZZOLLA's 100th anniversary, we recorded an exclusive Violin for Tango Jewel with lessons, performances, and minus-one tracks.