A Brief Introduction to the Concept of Classicism in Music

Part II

by Dr. Patrick J. Brill, Ph.D.

Another Aspect of Classicism: Art Perfecting Nature

In Part I of this essay, we examined the core of the principles of classicism, which focused on the concept of art imitating nature. Another important corollary of this concept should be added: realism and perfection—that is, the idea of art perfecting nature. The ancient Greeks envisioned a natural realism, but with the artist surpassing the imperfections of nature to achieve the impression of real perfection.

A Classic Composition

Another sense of “classic” is that predicated of a great, lasting, “immortal” composition, as in the “classics” of the great compositional masters. In these works, of course, the characteristics of classicism are absolutely essential. However, there are other elements and conditions necessary to create a great classic: these include the test of time, a high degree of artistic integration, the expression of profound, universal emotions, true genius, and moral correctness, among others.

Furthermore, utilizing classical principles does not guarantee that the work will be a true classic, as European libraries are replete with the works of well-trained classical composers who wrote many classical-style pieces, but who never composed a genuine classic.

Categories of the Fine Arts

There are two general classes of the fine arts: performing arts, such as theater, music and dance; and non-performing arts, which include painting, sculpture, and architecture. Others could be added, but these are the most traditional. The rest of this essay will touch very briefly on ancient Greek music, as well as a few examples of the application of classical principles to the music of several style periods in modern European music history.

Greek Music

Unfortunately, only about sixty fragments of ancient Greek music are extant, with one complete composition surviving: the Song of Seikilos, a song and poem of tribute by a husband to his deceased wife. The only other evidence of ancient Greek music that has survived is the numerous Greek music theory treatises.

This lack of music examples, which also includes no surviving music from ancient Rome, makes it difficult to have a real understanding of how the Greeks and Romans applied these principles to their music. How then, are we to determine the application of classical principles to music? The answer is Neo-classicism.

Neo-Classicism

Neo-classicism, which literally means “new classicism,” is a conscious revival, and practical application of the classical principles of ancient Greece and Rome in another time and place. After the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 A.D., much of the culture of Greco-Roman civilization was lost for several centuries.

Fortunately, the high Middle Ages in Europe began to see the early recovery of some of these lost treasures of the ancients; but it is the Humanist movement of the Italian Renaissance that recovered and translated the bulk of these works.

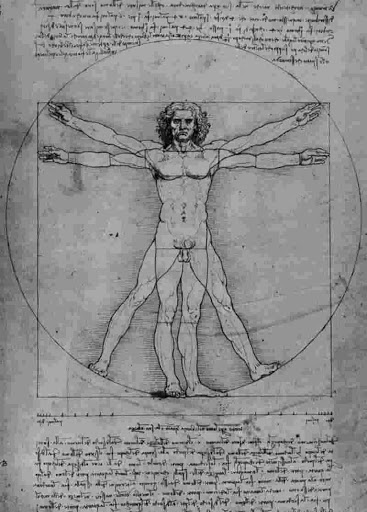

This knowledge became widespread and many artists and composers studied and imitated the ancients, and through this process discovered anew these basic principles. Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” from his Notes, is a stellar example.

The Renaissance

The pinnacle of 16th Century high Renaissance sacred music is the “ars perfecta,” which is embodied in the great sacred works of such composers as Palestrina, Victoria, Byrd, and Lassus. This style, which is mostly found in Masses and motets, manifests the principles of classicism particularly in two realms of composition: the dissonance treatment, and the melodic structure.

The dissonance treatment reveals the careful balance and proportion between consonant and dissonant harmonies, ensuring that dissonance is resolved systematically by consonance, while the melodic structure balances stepwise motion with leaps, as well as with ascending or descending leaps of large intervals that would then be balanced by immediate stepwise motion in the opposite direction.

Baroque Music: Opera and the Florentine Camerate

In theater, the ancient Greeks left us a great repertoire of tragedies, such as Oedipus Rex, Antigone, and others by such great tragedians as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Aristotle goes into great depth in his Poetics concerning the aesthetic goals and classicism of these Greek tragedians, such as the proper proportions and integrity of the plot, the imitation of the causes and effects of human actions, and the aesthetic effect of catharsis engendered by the creation of pity and fear in the audience.

The Florentine Camerata, a group of artists, academics, and other literary cognoscenti that resided in Florence, Italy in the late 16th and early 17th Centuries, contemplated a revival of ancient Greek tragedy, which they believed was sung with musical accompaniment. Since little was known of actual Greek music, the composers of the Florentine Camerata used the secular style of the late Renaissance, as featured especially in the Italian madrigal, for its musical style. Along with the drama of the plot, these artists believed that they had revived ancient Greek tragedy. This “new” genre became known as Opera.

Classicism in the Classical Style Period

The Classical style period, which includes the music of Mozart, Haydn, and early Beethoven, featured a number of applications of the principles of classicism, such as symmetrical phrase structures, including the well-known “antecedent-consequent” phrase, architectonic phrase structure, and the use of Sonata form, a tripartite design with exposition, development, and recapitulation sections. In this form, themes and harmonic events from the exposition are skillfully balanced with analogous events in the recapitulation, situated between a contrasting and dramatic development section that culminates in the apex of harmonic tension for the entire movement.

Classicism in the Romantic Period

The greatest exponent of classicism in the Romantic period was the German composer, Johannes Brahms. The music of Brahms exemplifies the ideal of preserving the principles of classicism from the Classical period, but adding more instruments to the orchestra, using more complex chromatic harmonies, and enlarging the Classical forms, such as the use of expanded Sonata form, and expanded Sonata-Rondo form.

Final Thoughts

It is my sincere hope that this all-too-brief sketch of the fundamentals of classicism will inspire others to explore these principles further, and in time, lead to a much-needed Neo-classical revival in this 21st Century.

About the author

Dr. Patrick Brill holds a B.A. degree in Philosophy from the College (now University) of St. Thomas, and a B.A. degree in Music from the University of Minnesota, where he studied piano, music history, and music theory/composition.

He earned a Master’s of Music in music history from the University of Northern Iowa and holds a Ph.D. in historical musicology from the University of Kansas. He has published a book on sacred music and authored serval musicological articles.

Dr. Brill has taught music history at the University of Kansas, the University of Missouri-Kansas City, Rockhurst College, Valencia College, Barry University, Columbia College, and Eastern Florida State College. He currently teaches music history at Valencia College in Orlando, Florida. Dr. Brill has also taught private piano, as well as music theory/composition for many years.

Dr. Patrick Brill has composed numerous classical-style compositions including a cappella vocal works, instrumental chamber compositions, symphonic orchestral pieces, and compositions for both choir and orchestra. Website